Has Seattle traffic suddenly gotten a lot worse, or is it just my skewed perception? I take the Sound Transit 510 express bus from Everett to Seattle every day for work and in the past few weeks I’ve experienced some really excruciating commutes, particularly in the morning on the way into Seattle.

Seattle’s worsening traffic has been the subject of a number of recent articles in both the Seattle Times1 and the Everett Herald2 based on a recent Corridor Capacity Report published by the Washington State DOT. However, this report only covers data through 2013, and my impression has been that things have gotten considerably worse just in the last few weeks.

As it turns out, I just so happen to have been collecting detailed data about my commute for over three years. Since late 2011 I’ve been logging the time at fourteen points along my way to work in the morning and on the way home in the evening. Using this data set, I can visualize my commutes to see if the last few weeks have seen anything truly out of the ordinary.

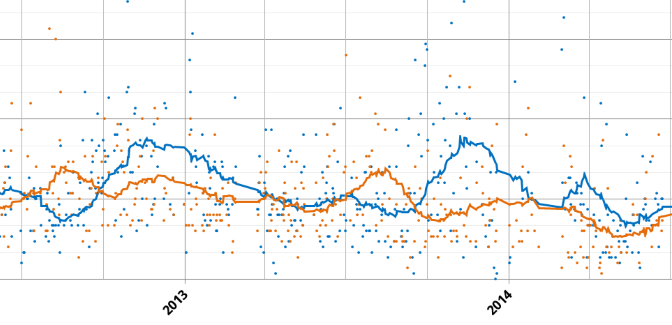

The plot below has a blue dot indicating the time between boarding the bus in Everett (at 34th & Broadway or 38th & Broadway) every morning and disembarking on one of the first stops (Stewart Street) in downtown Seattle. Orange dots represent the time spent on the bus in the evenings going the reverse direction. The lines are a 30-day rolling average.

After peaking at 56 minutes in late 2012, then peaking at 54 minutes in late 2013, the 30-day average morning commute has risen to an hour and five minutes as of November 3rd.

In fact, six of the ten worst morning commutes I’ve experienced in the last three years have been in just the past three weeks.

| Date | AM Ride |

|---|---|

| 2014-10-20 | 01:49 |

| 2014-10-28 | 01:47 |

| 2014-11-04 | 01:46 |

| 2014-09-24 | 01:44 |

| 2013-11-08 | 01:40 |

| 2012-11-19 | 01:35 |

| 2014-10-23 | 01:33 |

| 2014-10-21 | 01:33 |

| 2012-05-31 | 01:33 |

| 2012-11-01 | 01:33 |

Probably due to the combination of the onset of rainy weather, less daylight, and other factors, the fourth quarter of each of the last three years has seen considerably worse morning traffic than the rest of the year, but this so far year it has been absolutely dreadful.

Interestingly, evening traffic in the opposite direction over this same period has not seen any significant increase compared to last year.

Hopefully the last few weeks have just been a series of terrible flukes, rather than the beginning of a trend of consistently nightmarish morning commutes.

At least I always get a seat on the bus, where I can sleep, read Reddit, or write blog posts like this.

[2] – Numbers don’t lie — traffic is terrible and getting worse, Everett Herald, 2014-11-03

There’s been quite a bit of press recently about a new “family robot” called

There’s been quite a bit of press recently about a new “family robot” called